Air Force Magazine June 2006, Vol. 89, No. 6For US airmen, the Long War with terrorists began on

|

||

|

|

|

|

| The scene on |

An aerial view of the destroyed

|

|

|

The Hour of Attack They were airmen of the 4404th Wing (Provisional). Their mission was to

enforce the no-fly zone over southern On that night, the 4404th’s wing commander was Brig. Gen. Terryl J. Schwalier—but not for long. Schwalier had just finished his one-year tour and was sitting at the desk in his room, on his last night in Saudi Arabia, writing a note to Brig. Gen. Daniel M. Dick, who was taking over the wing in the morning. Elsewhere, the commander of the 79th Fighter Squadron, out of Shaw AFB, S.C.,

was filling out promotion recommendation forms in Building 133. Members of the

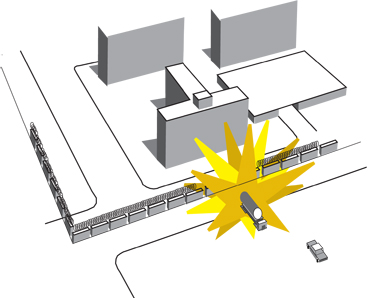

33rd Fighter Wing from Eglin AFB, Others were keeping watch. SSgt. Alfredo R. Guerrero was the security forces shift supervisor on duty that evening. He went up to the rooftop of Building 131 to check in with the two sentries posted there. While Guerrero was on the roof, the three security forces troops noticed a sewage tanker truck and a car enter the parking lot adjacent to Building 131. They watched the driver wheel the truck to the second-to-last row and then turn left, as if to depart the lot. Then, however, the truck slowed, stopped, and began backing up to the fence line, stopping again right in front of the center of Building 131’s north side. The driver and passenger got out and jumped into the waiting car. Even as the suspicious car sped out of the parking lot, the three USAF security forces personnel were in motion. They radioed in an alert and started the evacuation plan from the top floor. As one floor was departing, its residents would notify residents on the floor just below. Thus was Building 131 to be emptied in a “waterfall” fashion. They managed to notify residents on the top three floors, many of whom were fleeing down the building’s stairwell. At It was a blast like no other in the Gulf region—ever. In November 1995, a

terrorist car bomb had exploded in

Building 131 did not cave in completely, but that was only because it was made of prefabricated cubicles that had been bolted together. Had the apartment building been built in a more traditional manner with cross-support beams, the blast might have leveled it, causing the deaths of most residents. The first memories for many of the survivors in buildings nearest the blast began when they found themselves in the dark, thrown across their rooms or out into hallways. Now, as they struggled to understand where they were and what had happened, they shouted and called to each other, trying to discover who was alive and who was dead. In Building 131, a sergeant had been cleaning dust from under his bed. The mattress fell on him, partially shielding and protecting him. In Building 127, a squadron commander found a squadron mate sitting in a pool of blood with a dagger of glass in his thigh. In Building 133, nearly 400 feet from the explosion’s center, one of the officers who had been writing promotion forms was thrown 30 feet into the hallway. He looked up to see the roiling dust, fire, and smoke coming from the direction of Building 131. Oak doors were blown off their hinges, and furniture was jumbled. All windows and frames within 1,500 feet of the blast crater were blown out. Fears of another explosion, gas attack, or building collapse darted in and out of the minds of the airmen. When occupants of the most severely damaged buildings attempted to move, they felt the shards of glass crunch around them. Nearly all of the hundreds of injuries that night included lacerations from broken glass. The airmen had to get out of the dark and devastated buildings. Alerted by Guerrero and his team, many were already moving in the stairwells when the bomb went off.

Across the compound, Schwalier felt plate glass shatter over his back as the blast wave blew out his window, frame, and heavy curtains. Through the hole in the wall he saw the fireball and smoke. He pounded on the door of the joint task force commander, Maj. Gen. Kurt B. Anderson, who had traveled to Dhahran for the next day’s change of command ceremony. Then he raced out of the building to assess the damage. Hundreds of people were moving away from the northeast corner. “They’re coming through the wall,” squawked an unknown voice over the wing’s FM radio bricks. Observers near the north perimeter saw figures in white robes moving through the compound in the chaos. A hundred yards back, at Building 127, airmen began picking up the wounded and moved them toward the interior of the compound for safety. The first casualties arrived at the clinic just a few minutes after At For a time, Gen. Ronald R. Fogleman, the Air Force Chief of Staff, spent a day talking with airmen and visiting the wounded. At one of the small dispensaries, a young airman was so intent on removing stitches that she didn’t even look up at the hubbub when the Chief stopped in. Fogleman gave her a spot promotion. In mid-July, retired Army Gen. Wayne A. Downing, a former commander of US Special Operations Command, arrived to head up an investigation at Defense Secretary William J. Perry’s request. Schwalier showed him the devastated buildings. It was hot, with temperatures in the buildings near 112 degrees and a horrible smell rising out of the heat and rubble. “A smell of death,” Schwalier called it. “Literally.”

The first, which attracted much publicity, was the so-called hunt for “accountability.” The House National Security Committee had a team on the ground quickly, and it produced its report within weeks. owning’s probe was the first of three major investigations conducted by the

military. Downing’s report found fault with Schwalier and others, made

numerous recommendations, and called for leaving disciplinary actions to the

chain of command. Two subsequent Air Force reports followed up with additional

force protection tasks. Neither of those two USAF investigations held any single

individual responsible. Ultimately, Pentagon leadership, in the person of new

Secretary of Defense William S. Cohen, focused on the commander, Schwalier, who

was blamed for, in effect, failing to prevent an act of war. He took the fall

and resigned on The second question—who did the foul deed—was investigated along an

entirely different path. Within days, 70 FBI agents were in However, the Saudi leadership was intensely sensitive about allowing outside

investigators to dig around for clues. It was not until November 1998 that the

FBI gained the access it wanted to suspects held by When it came, the federal indictment spelled out a compelling story. Thirteen

members of Hezbollah cells based in At the time of the Hezbollah planning, however, In January 1996, Schwalier and his commanders evaluated security at But as the FBI found, plans for the attack were thorough and sophisticated.Leaders of the military wing of the Saudi branch of Hezbollah began to prepare a bomb plot in 1993, and the plotting intensified over the next three years. Step one was to initiate surveillance of American activities in the kingdom.

In 1994, the terrorists narrowed down the target list to several installations

in eastern

The FBI found that it was Al-Mughassil who chose Then their plan almost went awry. Another operative, Fadel Al-Alawe, tried to

bring in more explosives from Even with a diminished team of terrorists, however, Al-Mughassil had enough people and enough plastic explosives to go ahead with the attack. As listed in the indictment, a group of nine carried it out. In addition to Al-Mughassil, they were Ali Al-Houri, Hani Al-Sayegh, Ibrahim Al-Yacoub, Abdel Karim Al-Nasser, Mustafa Al-Qassab, Abdallah Al-Jarash, Hussein Al-Mughis, and an unidentified Lebanese man. No specific word of the Hezbollah group’s plans reached the Americans

trying to defend Then-Secretary of Defense William Perry later acknowledged that the “It did not provide the user with any specific threat, but rather laid out a wide variety of threat alternatives,” Perry went on. “My assessment is that our commanders were trying to do right, but, given the inconclusive nature of the intelligence, had a difficult task to know what to plan for.” |

||