Bill Clinton

White House suppressed evidence of Iranís terrorism

Sent secret cable accusing Tehran of

1996 Khobar Towers attack, but kept it from public

By John Solomon - The Washington

Times - Monday, October 5, 2015

Bill Clinton's

administration gathered enough evidence to send a top-secret communique accusing

Iran of facilitating the deadly 1996 Khobar Towers terrorist bombing, but

suppressed that information from the American public and some elements of U.S.

intelligence for fear it would lead to an outcry for reprisal, according to

documents and interviews.

Before Mr.

Clinton left office, the intelligence pointing toward Iran's involvement in the

terror attack in Saudi Arabia that killed 19 U.S. servicemen and wounded

hundreds was deemed both extensive and "credible," memos show.

It included FBI

interviews with a half-dozen Saudi co-conspirators who revealed they got their

passports from the Iranian embassy in Damascus, reported to a top Iranian

general and were trained by Iran's Revolutionary Guard (IRGC), officials told

The Washington Times.

The revelations

about what the Clinton administration knew are taking on new significance with

the recent capture of the accused mastermind of the 1996 attack, which has

occurred in the shadows of the U.S. nuclear deal with Iran.

Ahmed

al-Mughassil was arrested in August returning to Lebanon from Iran, and his

apprehension has provided fresh evidence of Tehran's and Hezbollah's involvement

in the attack and their efforts to shield him from justice for two decades, U.S.

officials said.

Former FBI

Director Louis Freeh told The Times that when he first sought the Clinton White

House's help to gain access to the Saudi suspects, he was repeatedly thwarted.

When he succeeded by going around Mr. Clinton and returned with the evidence, it

was dismissed as "hearsay," and he was asked not to spread it around

because the administration had made a policy decision to warm relations with

Tehran and didn't want to rock the boat, he said.

"The bottom

line was they weren't interested. They were not at all responsive to it,"

Mr. Freeh said about the evidence linking Iran to Khobar.

"They were

looking to change the relationships with the regime there, which is foreign

policy. And the FBI has nothing to do with that," he said in an interview.

"They didn't like that. But I did what I thought was proper."

Mr. Freeh made

similar allegations a decade ago when he wrote a book about his time in the FBI.

He was slammed by Clinton supporters, who accused him of being a partisan,

claimed the evidence against Iran was inconclusive and that the White House did

not try to thwart the probe.

But since that

time, substantial new information has emerged in declassified memos, oral

history interviews with retired government officials and other venues that

corroborate Mr. Freeh's account, including that the White House tried to cut off

the flow of evidence about Iran's involvement to certain elements of the

intelligence community.

Chief among the

new evidence is a top-secret cable from summer 1999 showing that Mr. Clinton

told Iran's new and more moderate president at the time, Mohammad Khatami, that

the U.S. believed Iran had participated in the Khobar Towers truck bombing.

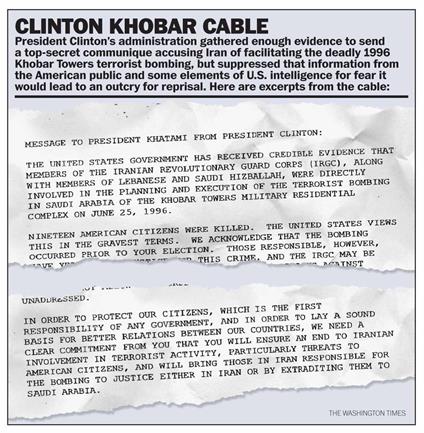

"Message to

President Khatami from President Clinton: The United States Government has

received credible evidence that members of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard

Corps. (IRGC) along with members of Lebanese and Saudi Hizballah were directly

involved in the planning and execution of the terrorist bombing in Saudi Arabia

of the Khobar Towers military resident complex," reads a declassified

version of the cable obtained by the National Security Archives group.

"The United

States views this in the gravest terms," the cable added. "We

acknowledge that the bombing occurred prior to your election. Those responsible,

however, have yet to face justice for this crime. And the IRGC may be involved

in planning for further terrorist attacks against American citizens. The

involvement of the IRGC in terrorist activity and planning aboard remains a

cause of deep concern to us."

A spokeswoman

for Mr. Clinton declined to comment on the record for this story.

Today, there is

little doubt in U.S. circles that Iran and its Saudi Hezbollah arm participated

in the deadly Khobar Towers attack. Shortly after Mr. Clinton left office, an

indictment was issued against Mr. Mughassil that cited the IRGC's assistance.

And in 2006 a federal judge ruled in a civil case brought by families of the

Khobar victims that Iran was liable for hundreds of millions of dollars for its

role in the attack.

The revelations

about what Mr. Clinton knew about Iran's involvement and what was kept from the

public could have implications on the campaign trail for his wife Hillary's

emerging Iran policy. Seeking the 2016 Democratic presidential nomination, Mrs.

Clinton has embraced the controversial nuclear deal she helped start with Iran

as secretary of state but also declared she wouldn't hesitate to use military

force if Tehran cheats.

It was the

specter of public pressure for such a military engagement, however, that

concerned her husband's White House after a link to Iran in the Khobar Towers

case was established.

Former aides

told The Times that Mr. Clinton originally ordered the military to create a

contingency plan for a formidable retaliatory strike on Iran, and in 1997 gave

permission to the CIA to conduct Operation Sapphire that disrupted the

activities of Iranian intelligence officers in several countries.

But with the

1997 election bringing about a new moderate leadership in Tehran, Mr. Clinton

tried instead to handle the matter privately in summer 1999, hoping that a new

Iranian leader at the time would renounce terrorism and cooperate in the Khobar

case after signaling a desire to moderate relations with America.

But Tehran

responded with a harsh denial, backed by its more radical theocratic ruling

elite, and it even threatened to make public the cable Mr. Clinton had sent the

Iranian leader. At the same time, the Iranians also made clear in their response

that they did not harbor ill will or intention against the United States at the

present time.

The threat of

going public alarmed top U.S. advisers, who feared the disclosure would lead to

public pressure inside the United States to retaliate against Iran militarily or

diplomatically, contemporaneous memos show.

"If the

Iranians make good on their threats to release the text of our letter, we are

going to face intense pressure to take action," top aide Kenneth Pollack

wrote in a Sept. 15, 1999, memo routed through White House aide Bruce Riedel to

then-National Security Adviser Sandy Berger.

Mr. Riedel, who

was instrumental in facilitating the top-secret cable to Iran, and Mr. Pollack

are now both scholars at the Brookings Institution. They did not return calls

and emails Monday seeking comment. But in his 2014 book, Mr. Pollack

unequivocally linked the Khobar attack to Iran.

"The 1996

Khobar Towers blast was an Iranian response to an $18 million increase in the

U.S. covert action budget against Iran in 1995," Mr. Pollack wrote.

"The Iranians apparently saw it as a declaration of covert war and may have

destroyed the Khobar Towers complex as a way of warning the United States of the

consequences of such a campaign."

Flow of intel

restricted

Former Clinton

aides, speaking on condition of anonymity, said the evidence pointing to Iranian

involvement had become substantial by 1999. Still, some in the administration

worried it was not solid enough to warrant military action, and might have been

exaggerated by Saudi Arabia and its Sunni-Shia rivalry with Iran. They argued

that working for moderation with Mr. Khatami was a better alternative than

blaming it for an attack that happened under an earlier regime, the former aides

said.

Others believed

there was little doubt Tehran was involved but worried about the American

public's appetite for a military action against Iran and the possibility it

would unleash a wider terror war, the former aides explained.

Whatever the

case, the White House opted to downplay the concerns, suggesting in public that

the evidence linking Iran was "fragmentary" or uncertain. Behind the

scenes, steps were also taken to restrict the flow of any further evidence that

Iran assisted the Khobar attack, according to interviews with law enforcement

and intelligence officials.

At the time, the

FBI and the State Department's intelligence arm were gathering significant new

cooperation from Saudi authorities that pointed toward Iranian involvement. But

suddenly the flow of information was stopped, officials told The Times.

"We were

seeing a line of traffic that led us toward Iranian involvement, and suddenly

that traffic was cut off," recalled Wayne White, a career intelligence

officer inside the State Department from 1979 to 2005 who served as deputy

director of the State Department's Bureau of Intelligence and Research's Office

of Analysis for the Near East and South Asia.

Mr. White and

other colleagues first disclosed the stopped flow of intelligence during an oral

history project for a career diplomats group, and he agreed to recount the

details to The Times. During the Clinton administration, his team was

responsible for intelligence inside State for Iran, Iraq, the Middle East and

North Africa, and was taking a lead role in the Khobar probe as well as

evaluating other regional terrorism threats.

When the

intelligence flow stopped on Iran's involvement in Khobar, Mr. White said he

made a "very heated demand up the chain of command."

"We did not

sit idly by and accept this," he said in an interview. "When we found

out we and the originating agency were being denied intelligence, we went

upstairs to the front office to find out what was happening and to let them know

we were outraged."

Mr. White said

his team tried several different ways to try to get intelligence flowing again,

including seeking a deal to restrict the information to the secretary of state

or a senior deputy. Eventually, he said, he learned the blockade had been

ordered by Mr. Clinton's top national security aide.

"We later

found out the stream had been cut off by Sandy Berger, and the original agency

producing the intelligence was struggling to work around the roadblock," he

said.

Mr. Berger, who

later was convicted of trying to smuggle Clinton-era classified documents about

terrorism out of the National Archives, now works for a consulting firm in

Washington. His office said he was unavailable for comment.

Mr. White's

account was confirmed to The Times by foreign diplomats and several U.S. law

enforcement officials with direct knowledge of the matter, including former FBI

Director Freeh.

Mr. Freeh said

when his agents returned from Saudi Arabia in 2000 with clear-cut statements

from the co-conspirators about Iran's involvement, he went to see Mr. Berger and

was instructed not to disseminate the information.

"He asked,

'Who knows about this?' And I said, 'Excuse me?' 'So, who knows about it?' he

says. 'Well,' I said, 'the attorney general of the United States, me, you, about

50 FBI agents and the Saudi government,'" Mr. Freeh recalled.

"'Well,' he

said, 'it's just hearsay.' And I said, 'Well, with all due respect, it's not

hearsay. It would be a statement by a co-conspirator in furtherance of a

conspiracy and would come into court under the rules of evidence,'" he

added.

Mr. Freeh said

he first began encountering resistance to making a case against Iran when he

first wanted to send the agents to Saudi Arabia a year earlier.

"What we

were told by the Saudis was the only way that we can do this is if your

president asks the king or the crown prince for this access," he said.

"And if so, we can probably deliver it at that level. But we can't do it at

your level.

"So we

spent a number of months, more than a number of months, writing talking points

for the president. We'd give them to Sandy Berger, and the president would then

have whatever meetings he would have with the king or crown prince. And the word

kept coming back to us that he never raised the talking points.

"I'd go

back to the White House and say we are told the talking points, the requests,

weren't raised. And we would get a variety of different answers," he

continued. "But the bottom line was we couldn't get the president to raise

this. So what I did was I contacted former President George H.W. Bush. He had a

very good relationship with the Saudis. I explained to him what my dilemma was

and asked if he would contact the Saudis. And he did."

Mr. Freeh said

he witnessed another example of the Clinton administration showing deference to

Iran that he feared risked national security.

"They were

encouraging me not to do surveillances on the cultural teams and athletic teams

that were starting to come in from Iran," he said. "And I refused as

director, saying we had good evidence that the Iranians had put their agents on

these wrestling teams and they were coming into the U.S. to contact

sources."

Mr. White said

his intelligence analysts didn't want Iran to have been behind the Khobar Towers

attack because it would have serious long-term ramifications for America. But

once the evidence established a link, it was wrong for the information to be cut

off for political reasons, he said.

"It

polluted the entire intelligence process, which is not supposed to be interfered

with in any way with political priorities," he said. "You cannot

provide your intelligence community selective intelligence without corrupting

the process, and that was an outrage."

© Copyright

2015 The Washington Times, LLC. Click here for reprint permission.